Immortality of the Spirit: Chinese Funerary Art from the Han & Tang Dynasties

The Bellarmine Museum

April 12, 2012 - June 6, 2012

For the ancient Chinese, life in the afterworld was as important as one's existence on earth. For this reason the dead were laid to rest in tombs intended to replicate earthly palaces in all their splendor. They were also adequately provisioned by surviving family members with mingqi, or "spirit articles," for the deceased's journey into the afterlife.

Fairfield University's Bellarmine Museum of Art will explore this fascinating subject in its new exhibition, "Immortality of the Spirit: Chinese Art from the Han and Tang Dynasties," which features thirteen pottery funerary objects from the Han (206 BCE - 220 CE) and Tang (618 - 907 CE) Imperial dynasties. A small catalogue, co-authored by Mr. Swergold and Dr. Ive Covaci (Adjunct Professor of Art History at Fairfield University and a specialist in Asian Art), is available in the galleries.

The earliest Chinese tomb figures and furnishings date back to the Neolithic period (10,000 - 2,000 BCE). The popularity of such objects increased during the lengthy Han dynasty before reaching its zenith under the highly cosmopolitan Tang Dynasty. Considered one of the "golden ages" of Chinese civilization, the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) was an era of relative peace, prosperity, and Imperial expansion, which was marked by great advances in poetry, music, calligraphy and the visual arts. Trade also flourished in the outward-looking Han Empire, which fell in 220 CE. Centuries of disunity followed until the 7th century, when the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907 CE) ushered in another long period of stability and prosperity. Its capital, Chang'an (modern day Xi'an) was the largest and most sophisticated city in the world at that time, with a population (including immigrants from as far away as Persia and Syria) of some one million people in the mid-8th century. Art and culture flourished under the dynasty's extensive court patronage, and a new interest in naturalism was expressed in painting and sculpture, including funerary objects.

Clay tomb figurines proliferated in the Han Dynasty, replacing an earlier tradition of human and animal sacrifice. Despite this humane shift, the basic principle remained the same: everything needed in life was also needed in death, including horses, chariots, farm animals, guards, attendants, entertainers, and vessels for lavish banquets, as the pieces on display in the Bellarmine - including a Seated Story Teller and a Figure of a Dancer (both Han) - illustrate. These replicas, like all mingqi, were deliberately made to appear distinct from the "real thing" by alterations in material, color, size, technique, or function. It is by understanding this broader context that visitors to the Bellarmine can gain a deeper appreciation of the objects showcased in "Immortality of the Spirit ..." and the cultures that created them.

While personal possessions and items used in daily life could be interred with the dead, the majority of grave goods were created specifically for funerary purposes. Indeed burial figures and furnishings were exhibited during lavish funerary rites before being sealed in the tombs for which they were intended. These objects, like the tombs themselves, communicated the social status of the occupant. The wealthier the family, the more elaborate the tomb and the finer - and more numerous - the funerary objects that accompanied the deceased on his or her journey into the next world. Tombs were also seen as gateways to everlasting life. Thus, symbols of immortality commonly appear on Han and Tang funerary objects, such as the cloud-filled mountain landscape representing the abode of the immortals on the fine Hill Jar (Han Dynasty) exhibited in the museum's show.

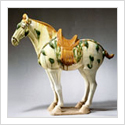

The market for funerary goods was such that workshops had to rely on molds in order to keep pace with demand. Fine details on tomb figures and vessels were sometimes shaped by hand, but often decoration (such as that of the Green Glazed Jar, or Hu (Han Dynasty), at the Bellarmine) was also molded. Though the shapes of ceramic vessels, in particular, often echo metal prototypes, burial figures were made from a variety of media, including clay, jade, bronze, gold, silver, wood, textile, or stone. Clay objects, like the ones showcased at the Bellarmine, could be painted, unpainted, or glazed. Remarkable in this context is the stunning Sancai Glazed Horse (Tang Dynasty), on view in the museum's galleries. Sancai (or three color) glaze was applied to objects by dipping, pouring, and painting. Heads and extremities of figures were often left unglazed, so that details could be painted directly onto the earthenware. The presence of such objects in tombs was a mark of high status, and hence restricted to imperial and elite tombs.

The work of Tang artisans, in particular, reflects the influence of the many cultures with which they came into contact both in their capital city of Chang'an and elsewhere. It is not unusual, for example, to find exotic symbols, motifs and shapes more closely associated with the arts of India, Persia, Syria and even Greece in Tang art. The Pair of Sancai Glazed Grooms (Tang) on view at the Bellarmine, for example, have Persian facial features; apt reminders not only of the international flavor of this dynasty but also of the historical fact that the Tang emperors consolidated and maintained their martial power by importing horses - and horsemen - into China.

Artifacts like those in the Bellarmine Museum of Art's exhibition provide great insights into daily life during the Han and Tang Dynasties. They also remind us of how carefully orchestrated the burial rites and rituals were for a society with clearly delineated class hierarchies: the poor typically were buried with little more than small coins while the wealthy were accompanied by elaborate figures.

This exhibition has been made possible through the generosity of Jane and Leopold Swergold, who have lent both their objects and their expertise to this project. Further support was provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities: because democracy demands wisdom.